The Neurology in Shakespeare

By Lance Fogan, M.D.

The History of Neurology Award-

the American Academy of Neurology: 1988

pages 922-

Four centuries ago Shakespeare’s genius was presented to the world. “An oceanic mind,” “a mirror held up to mankind” -

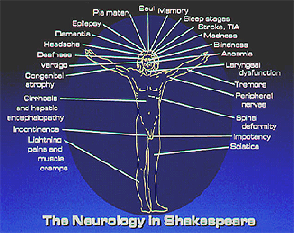

Many volumes and articles describing his medical knowledge have been written over the past two centuries. As a clinical neurologist the symptoms, signs, and diseases of the nervous system that appeared in the various characters in the plays, and in his poetry, are depicted in the Vitruvian figure below. Some depictions are forthright such as stroke, epilepsy, headache, vision and hearing abnormalities, vertigo, dementia, delirium, psychosis, sciatica, birth injuries of nerves, incontinence and impotency.

What are not so overt to the lay person for example, are very subtle, but highly accurate, descriptions of protein’s deleterious effect on an alcoholic with cirrhosis of the liver, and several of the complications of late stage syphilis. How they appear in his works are most fascinating, and I discuss them in my personal presentations to audiences and in my publications.

ALCOHOL and the BRAIN

In Twelfth Night brain decompensation by an impaired, cirrhotic liver that is incapable of metabolizing a protein load is highlighted in this exchange between Sir Toby Belch and his long-

This is among the first descriptions of hepatic encephalopathy, a condition taught to all medical students. Shakespeare may not have understood the mechanism of the brain dysfunction, but as a keen observer of life around him, it registered, and he accurately reported it.

EPILEPSY

In Othello, Othello is a known epileptic as stated by his trusted, but disloyal companion, Iago. Othello presents an actual seizure on stage, preceded by a severe emotional stress – Iago’s famous dropping of Desdemona’s handkerchief for Othello, her husband, to find causing him to fly into a jealous rage. Othello becomes confused, saying (Act IV, scene 1, line 41): “It is not words that shake me thus. – Pish! Noses, ears and lips? Is’t possible? – Confess? – Handkerchief? – O devil! (he falls in a trance).”

Iago then says: “…My lord is fall’n into an epilepsy. This is his second fit; he had one yesterday.”

Cassio, an observer, says: “Rub him about the temples.”

Iago responds: “No, forbear. The lethargy must have his quiet course. If not, he foams at the mouth, and by and by breaks out to savage madness. Look, he stirs. Do you withdraw yourself a little while. He will recover straight.”

Anyone familiar with complex partial seizures will recognize how classical Othello’s seizure is. Later in the play he murders his wife in a jealous rage. In our 21st century, who would not think that a criminal lawyer would have had Othello found innocent, or at least guilty of a far less serious charge, by telling the court that his client, a known epileptic, was not responsible for his action. He would especially have strengthened his case if a witness had testified that he had heard Desdemona crying out as she was being strangled (Act V, scene 2, line 40): “And yet I fear you; for you’re fatal then when your eyes roll so.”

The classical features of a complex partial seizure are featured in Shakespeare’s rendering: the aura initiated with emotional stress and the confusion and loss of awareness. Shakespeare must have witnessed many seizures in his fellow citizens in London because his observations are so accurate. Iago warns Cassio not to touch or try to restrain Othello fearing Cassio would then be in physical danger -

ANATOMY and SHAKESPEARE

How many lay people in the 21st century know that our brain contains chambers, called ventricles, which are filled with cerebrospinal fluid? Shakespeare did 400 years ago. In Love’s Labor’s Lost Holofernes says (Act IV, scene 2, line 66): “These are begot in the ventricle of memory…”

SYPHILIS

The neurological complications of the late stages of syphilis appear in several of the plays. Gummas of the hard palate, a particular inflammatory lesion specific to late syphilis, are implied in several of the plays, and especially in The Merchant of Venice. Here, Shylock (Act IV, scene 1, line 152) mentions: “…and others, when the bagpipe sings i’ the nose cannot contain their urine…”

The ‘bagpipe singing i’ the nose’ is interpreted as air escaping during speech through the hole pathologically produced by the gumma of late-

But most spectacular are the references to hoarse voice, known as “prostitute’s whisper,” and to lightning-

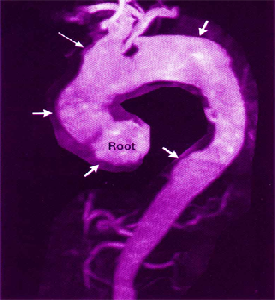

In the play one of Timon’s malignant tirades is directed at two prostitutes. He tells them (Act IV, scene 3, line 153): “…Give them (men) diseases” and …crack the lawyer’s voice, that he may never more false title plead nor sound his quillets shrilly.” It would be a challenge even for modern physicians casually reading the play to interpret these lines. Medical students learn that one of the complications of late stage syphilis is inflammation and weakening of the wall of the large main artery exiting the heart, the ascending aorta. Wrapping normally under this vessel is the left recurrent laryngeal nerve that innervates the left vocal cord. When the ascending aorta expands to the near-

MRI scan showing swollen aorta within the arrows

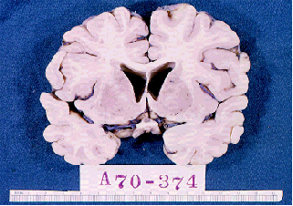

The neuropathological form of late stage syphilis, known as tabes dorsalis, affects the spinal cord. Only diabetes and tabes dorsalis cause lightning-

DEMENTIA

Dementia is a decline of intelligence from a previous level; notably represented today by Alzheimer’s disease, a degenerative process that occurs mostly in late life. Clinical neurologists can not surpass Shakespeare’s description of dementia in The Winter’s Tale. His exact same observations can be recorded in any modern general neurology/geriatric clinic as Polixenes states (Act IV, scene 4, line 390): “…Is not your father grown incapable of reasonable affairs? Is he not stupid with age and alt’ring rheums (aches and pains)? Can he speak? Hear? Know man from man? Dispute his own estate? Lies he not bed-

STROKE

Stroke and transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) are alluded to by Shakespeare four centuries ago that so entice our imagination with his clinically accurate description that it is simply dumbfounding. How could he use terms to describe stroke that focus on our concepts of the mechanism in the 21st century? Falstaff, in Part II Henry IV (Act I, scene 2, line 101), upon spying that the King is in sudden distress, says: “And I hear…his highness is fallen into this same whoreson (terrible) apoplexy (a sudden brain dysfunction), as I take it, is a kind of lethargy…a kind of sleeping in the blood, a whoreson tingling…It hath it original from much grief, from study and perturbation of the brain…” What Falstaff is saying is that some clinical change has suddenly happened to the king. Falstaff then states that the King’s blood slowed down – we can imagine a clot, a blockage of an artery supplying the brain, and when that happens, the King experiences tingling. Certainly this suggests a stroke to us today. And then to explain why it occurred, as patients and their families do today, Falstaff incorporates stress as what brought it on.

SHAKESPEARE'S MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE

We only can speculate how Shakespeare came by his knowledge. There were no medical journals, and very few books, which only wealthy educated people could afford. Lawyers have explored his legal knowledge that was demonstrated in the plays. They conclude that he must have been a lawyer because he used the terms and concepts so accurately. I have studied his neurological observations. Many of the other medical specialties have done the same, showing that he knew their fields, too. William Shakespeare? All the facts about that person can be written in one short paragraph; he was born in Stratford on April 23, 1564 and he died on the same date in 1616. Records show that he had several years of education in primary school, which stressed Latin, as a child in Stratford. He married, had children many of whom, if not all, including his wife, were illiterate. Records show that he did act, and he did own a theater company, in London; he retired successfully in 1611 to a very elegant house in Stratford. His famous will upon his death left his “second” best bed to his wife – the best bed apparently was reserved for guests in that society. But, significantly, the most prized possessions in Elizabethan England – books – were not mentioned.

Was SHAKESPEARE the AUTHOR?

Scholars know that the educated upper classes of that time would not have been associated with actors, acting, or with the theater. Thespian arts were disparaged by the elite. Did one of them “borrow” his name to disguise his, or her, playwrighting participation?

Did Shakespeare ever travel out of England? One-

So, there are many questions: did the person named William Shakespeare from Stratford write the finest, insightful, and most beautiful dramatic literature and poetry in the English-

Sir Toby Belch and Sir Andrew Aguecheek at drink